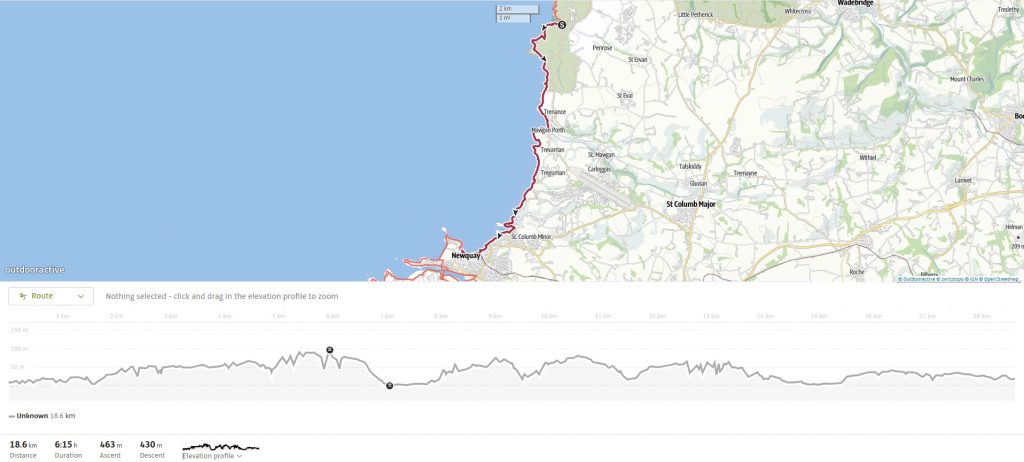

The South West Coast Path between Porthcothan and Newquay is a dramatic 18 km (11 mile) stretch of Cornwall’s north coast, rich in striking geology and sweeping views. From quiet coves and caves carved into the cliffs, to the towering sea stacks of Bedruthan Steps, this route combines exhilarating clifftop walking with long sandy bays and hidden traces of ancient history. Frequent descents into valleys add challenge, but the rewards are some of the finest panoramas in Cornwall.

SWCP 16: The Walk

Moderate —Moderate

15 July 2025

From Porthcothan to Park Head

Today was a wild and very windy day. Within minutes, I’d nearly lost my hat several times.

After another night at the Farmers Arms, we left the car in Newquay and caught the crowded 10 am bus back to Porthcothan — popular because it stops at the airport.

From the bay’s edge, we climbed gently out of the village, soon regaining the high cliffs. Behind us lay the wide sweep of Porthcothan Bay, its sand flanked by sea stacks and caves sculpted by the Atlantic. Ahead, waves crashed against the Trescore Islands.

The path undulated around headlands before dropping to the rocky inlet of Porth Mear. A small bridge crossed the stream, then the climb began again towards Park Head. From here, the first glimpse of the legendary Bedruthan Steps appeared in the distance.

Bedruthan Steps – Cornwall’s Giant Causeway

At Pentire Steps the famous sea stacks came fully into view — jagged rock towers rising from the beach like stepping stones. Legend tells of a giant named Bedruthan who used them to stride across the bay. In reality, they are the remnants of ancient headlands carved by relentless Atlantic waves along natural fault lines.

We followed the cliff path south, pausing at the National Trust’s viewing platform where the panorama was breathtaking. Access to the beach has been closed due to erosion and unstable cliffs, but from above the drama of the stacks is unforgettable. Queen Bess, Redcove Island, and other formations each stand as sculpted fragments of Cornwall’s geological past.

After climbing the 50-odd steps back to the clifftop we passed the National Trust car park and continued around Carnewas Point, where the paths are wide and even wheelchair accessible.

The Bedruthan Steps coastline showcases some of Cornwall’s most dramatic geology. Its sea stacks and folded cliffs are carved from Devonian slate and sandstone, laid down over 380 million years ago and later twisted by the Variscan Orogeny1.

The relentless Atlantic has eroded this coastline along natural faults and bedding planes, creating arches, caves, and the iconic sea stacks like Queen Bess and Redcove Island. Each is a fragment of a former headland, slowly being reshaped by the sea. The cliffs are unstable, prone to rockfalls and landslips, and access to the beach is currently closed for safety.

The area is also known for rare Devonian fossils, including corals and ancient marine life, making it a rich site for geological discovery within the Cornwall AONB.

Mawgan Porth and Berryl’s Point

Beyond Trenance Point the coast curved towards Mawgan Porth. With the tide low, we crossed directly over the beach — a welcome change from the cliffs and an opportunity for Roxie to have a run and a paddle— before rejoining the trail at the far end. A short scramble along a wall helped us avoid a stretch of busy road, and soon the Coast Path climbed steeply again towards Berryl’s Point.

Here, above Beacon Cove and Griffin Point, the earthworks of an Iron Age cliff castle are still visible, silent reminders of the people who once defended this headland.

Watergate Bay to Whipsiderry

The vast golden sweep of Watergate Bay soon opened out ahead, stretching for over two miles. We descended through a holiday complex, crossed a car park, and then climbed again on the far side. Beyond lay Whipsiderry Beach, where the rocky islet of Black Humphrey Rock recalls the name of a local smuggler.

Unfortunately, landslips had closed sections of the cliff path here, so we detoured briefly along the road before picking up the trail again towards Porth Island.

This area was mined for lead and iron. In fact, the name “Whipsiderry” originates from the mining terms “Whips” and “Derrick.”

Into Newquay

The final approach threaded between beach, road and headland. An OS map led us along the sands of Porth Beach — actually part of the King Charles Coast Path rather than the SWCP proper, which skirts inland. Eventually, the two routes rejoined, bringing us onto the clifftops above Lusty Glaze and then into Newquay itself.

The sun had finally broken through, transforming the grey skies into a bright afternoon as we reached the harbour. A fitting end to a long day’s walk of towering cliffs, sweeping bays, and some of Cornwall’s most iconic views.

Newquay, on Cornwall’s north coast, is one of the UK’s best-loved seaside towns. Known as Britain’s surfing capital, it’s famous for long sandy beaches like Fistral and Towan, dramatic clifftops, and lively harbour views. The town grew rapidly with the arrival of the railway in Victorian times, and its mix of golden bays, bustling cafés, and vibrant nightlife continues to draw visitors.

Beyond surfing, Newquay offers family attractions such as the zoo and aquarium, plus easy access to the South West Coast Path and the wildlife-rich Gannel Estuary. Its harbour still recalls a fishing heritage once tied to pilchards and herring, while the town blends coastal adventure with Cornish charm, making it a popular base for exploring the region.

Walk Summary: Newquay to Perranporth

- Distance: 19 km (11.8 miles)

- Elevation gained: 425m (1394 ft)

- Difficulty: Moderate – frequent ups and downs into valleys

- Moving Time: 4:18 hours Elapsed Time: 5:29 hours

- Highlights:

- Porthcothan Bay – sea stacks, caves and blowholes

- Porth Mear – rugged inlet with bridge crossing

- High Cove – sea-carved cliffs and natural arch

- Bedruthan Steps – iconic sea stacks and panoramic viewpoints

- Carnewas Point – National Trust maintained viewpoints

- Mawgan Porth – wide sandy bay, walkable at low tide

- Berryl’s Point – climb past Iron Age cliff castle remains

- Watergate Bay – 2-mile sweep of sand and surf

- Whipsiderry Beach – closed cliffs but views of Flory Island

- Porth Island & Beach – detour inland, then rejoin coastal views

- Newquay Harbour – final approach past Lusty Glaze and Tolcarne

- I asked ChatGPT about the Variscan Orogeny, and this is what it said. The Variscan Orogeny (sometimes called the Hercynian Orogeny) was a major mountain-building event that took place around 350–290 million years ago (late Devonian to early Permian periods).

It happened when several ancient continental blocks—mainly Laurussia (Euramerica) and Gondwana—collided, closing the Rheic Ocean in the process. The collision crumpled the Earth’s crust, producing a huge mountain chain that once stretched across what is now:

Southwest England and Wales

France (Massif Central, Brittany)

Spain and Portugal

Germany (Harz, Black Forest, etc.)

Parts of Eastern Europe and North Africa

Although the mountains have long since been worn down by erosion, the geological structures they left behind (folded and faulted rocks, granite intrusions, mineral veins, and coal basins) are still very evident today.

In the UK, for example, the Variscan Orogeny explains the folded strata and granite intrusions in Cornwall and Devon, and it set the stage for the region’s tin and copper mining heritage. ↩︎