This spectacular stretch of the South West Coast Path crosses the rugged heart of the Penwith Granite. It’s a journey through a landscape shaped by ancient molten rock, relentless Atlantic erosion, and the intense mining industry this rock foundation supported. The granite formed deep underground during the Permian period, around 290 million years ago.

Quick Summary (for the casual reader)

- Walkers can see high, blocky granite cliffs, dramatic rocky inlets, and extensive mining ruins (engine houses).

- The cliffs are made of granite—a light-coloured rock full of large crystals—which formed from slowly cooling magma deep beneath the surface.

- The cooling rock fractured and created mineral veins (lodes) rich in tin and copper.

- Relentless erosion stripped the overlying rocks and exposed the granite, which was then mined for centuries.

1. 🗿 General Description: The Core of Granite Country

This walk is defined by the unique character of granite—a light-coloured, coarse, and extremely tough rock that forms the high ground of the Penwith peninsula.

The geology can be simplified into two main materials, plus a few key exceptions:

The Blocky Cliffs (The Penwith Granite)

- Location: Dominates the entire walk, especially the headlands like Zennor Head.

- Appearance: This is a light, pale rock with large, visible crystals. It forms high, angular cliffs that break down into distinctive cuboid or blocky shapes.

- Composition: Formed from slow-cooled magma, consisting mainly of quartz, feldspar, and mica. This rock is extremely hard and forms the most prominent headlands due to its resistance to the sea.

The Original Rocks (Killas, Slates, and Volcanic Layers)

- Location: Visible in some coves, inlets, and inland moorland exposures, especially where the granite ends.

- Composition: These are the metamorphic slates and altered sedimentary rocks (known locally as killas).

- The Volcanic Clues: Mixed in with these original sediments are rocks that originated as ancient sea-floor volcanic material, such as altered basalts. When molten rock erupts underwater, it sometimes forms distinctive blobs called pillow lavas. Their presence confirms that the sediments were originally laid down in a basin near active volcanism millions of years before the granite ever intruded.

- The Effect: These softer rocks were squeezed and baked when the hot granite pushed its way up, but they offer glimpses of the much older, more varied geological history of the area.

The strength of the granite ensures the coastline remains wild, creating narrow rocky spines called zawns (gullies) and extensive rocky foreshores.

2. 💥 How This Landscape Came About: From Magma to Mines

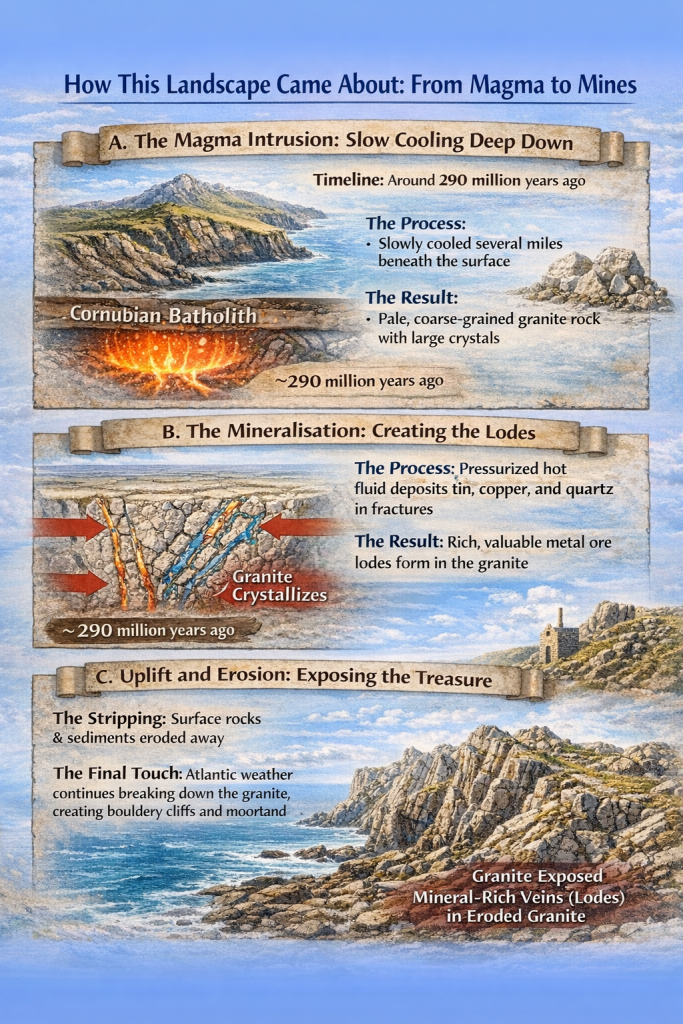

The present-day appearance of the cliffs is the result of three distinct geological events:

A. The Magma Intrusion: Slow Cooling Deep Down

The granite you walk on was not formed on the surface; it was once molten rock, or magma, part of the massive Cornubian Batholith beneath the whole of West Cornwall. The original rocks the magma intruded into were deep-sea muds, silts, and some ancient volcanic material (like basalt and pillow lavas), all laid down during the Carboniferous period.

- Timeline: Around 290 million years ago, a massive body of magma rose up but stalled several miles beneath the surface.

- The Process: Insulated deep underground, this magma cooled very slowly over millions of years.

- The Result: This slow cooling allowed the large crystals to form, creating the pale, coarse-grained granite rock.

B. The Mineralisation: Creating the Lodes

As the granite cooled and solidified, it fractured. This created the perfect channels for the next step.

- The Process: Highly pressurized hot fluids (water and chemicals) circulated through these fractures. These fluids leached out valuable metals like tin and copper from the surrounding rock.

- The Result: As the fluids cooled in the cracks, they deposited these metals and quartz, creating thin, ribbon-like mineral deposits called lodes or veins. These lodes were the entire reason for the area’s industrial revolution.

C. Uplift and Erosion: Exposing the Treasure

- The Stripping: Over millions of years, the softer rocks and sediments that once covered the granite were eroded and washed away. The tough granite was finally exposed, forming the high ground and cliffs you see today.

- The Final Touch: Relentless Atlantic weather continues to attack the granite, breaking it down along its natural cracks (joints) into angular blocks. This process creates the rough, bouldery path and the thin, stony soil of the inland moorland.

3. 🔎 What to Look For: Specific Sights Along the Path

This walk offers continuous geological and industrial sights that enhance your journey. Always observe cliffs from a safe, designated distance.

1. St Ives to Zennor Head (Classic Granite)

- Where to look: Along the initial section near Clodgy Point and around Zennor Head.

- What to spot:

- Blocky Cliffs: Observe the pale granite cliffs. They break down along their natural vertical joints into cuboid or blocky shapes.

- Salt Sculpture: Look at the surfaces of the exposed rock faces for patterns of honeycomb weathering—small holes and pits carved out by wind and salt spray exploiting the rock’s structure.

2. Gurnard’s Head (Structural Control)

- Where to look: From the path near the narrow neck of the headland, looking across the water or down into the inlets.

- What to spot:

- Jagged Inlets: Notice how the sea has exploited the deep, vertical cracks (joints) in the granite to carve out dramatic, straight-sided inlets and rocky spines, demonstrating the rock’s structural control over the coastline.

- Clitter Slopes: Look for piles of angular, loose granite boulders at the base of the cliffs or alongside the path. These clitter slopes are the result of weathering breaking the granite into cuboid blocks.

3. Bosigran to Levant (The Miners’ Clues)

- Where to look: In any exposed rock near the old mine workings and spoil heaps.

- What to spot:

- White Quartz Veins: Look for bright, clean white ribbons of quartz that cut sharply across the darker granite face. This quartz marks the trail of the mineral lodes that carried the tin and copper—this is what the miners were looking for.

- Iron Staining: Near the mine ruins, the granite often looks darker or stained with orange-brown rust. This is caused by iron in the mineral veins oxidizing (rusting) after the rock was exposed.

4. Levant to Pendeen (Submarine Mining and Heritage)

- Where to look: Stand near the famous engine houses of Levant and Geevor.

- What to spot:

- The Engine House Location: Observe that the engine houses are perched directly on the cliff edge. This is because the mineral veins they were following dipped steeply and ran straight beneath the seabed.

- The Spoils: Look at the large piles of mine waste (spoil heaps). The rock in these heaps is mostly crushed, grey granite and white quartz—the material that had to be dug out to get to the thin, valuable mineral veins.

- The Path and Soil: The entire path is rocky and the moorland soil is thin. This stony ground is the direct result of the hard, resistant granite weathering, which dictates why this area was always poor farmland but rich mining country.

Key Takeaway for the Walker

The high, blocky headlands are built from tough, resistant granite formed from ancient magma, while the iconic engine houses show how human history followed the thin, mineralized cracks created by that same geological event. The scenery you see is a direct result of this deep timeline.