This stretch of the South West Coast Path is arguably the finest coastal geology walk in Britain, showcasing the immense power of continental collision and the dramatic process of deep-sea sedimentation. The cliffs expose deep-marine rocks of the Upper Carboniferous period, deposited more than 300 million years ago.

Quick Summary (for the casual reader)

- Walkers can see perfect zig-zag folds, tilted strata, ripple marks, faults, and other dramatic features — especially around Millook Haven.

- The cliffs are made of layers of sandstone and shale laid down in a deep-water basin around 300 million years ago.

- Huge underwater sediment flows created thick sand layers; quiet periods left thin mud layers.

- Millions of years later, a massive continental collision folded and crumpled these rocks.

1. 🏞️ General Description: A World-Class Geological Showcase

The towering, dark cliffs between Bude and Crackington Haven are composed of rocks from the Carboniferous Period, laid down between roughly 310 and 300 million years ago.

The geology can be simplified into two main groups, which you will walk across:

The Striped Cliffs of Bude (The Bude Formation)

- Location: Dominates the cliffs around Bude, including Compass Point.

- Appearance: This rock sequence is characterized by thick, repetitive, or “striped” bands of rock.

- Composition: Alternating layers of hard, pale sandstone and softer, darker shale (or mudstone). The hard sandstones resist erosion and form the prominent ridges and headlands.

The Darker Cliffs of Crackington (The Crackington Formation)

- Location: Dominates the cliffs south of Widemouth Bay towards Crackington Haven.

- Appearance: As you walk south, the cliffs gradually become darker and the rock layers are visibly thinner and more intensely crumpled.

- Composition: Primarily thinner-bedded shales and siltstones. These softer rocks erode more easily, often creating the steep, secluded bays and coves.

The sheer thickness of these sediments—estimated to be over 1.3 kilometres deep—tells a story of continuous, rapid deposition over millions of years.

2. 💥 How This Geology Came About: From Deep Sea to Mountain Range

The present-day appearance of the cliffs is the result of two colossal events:

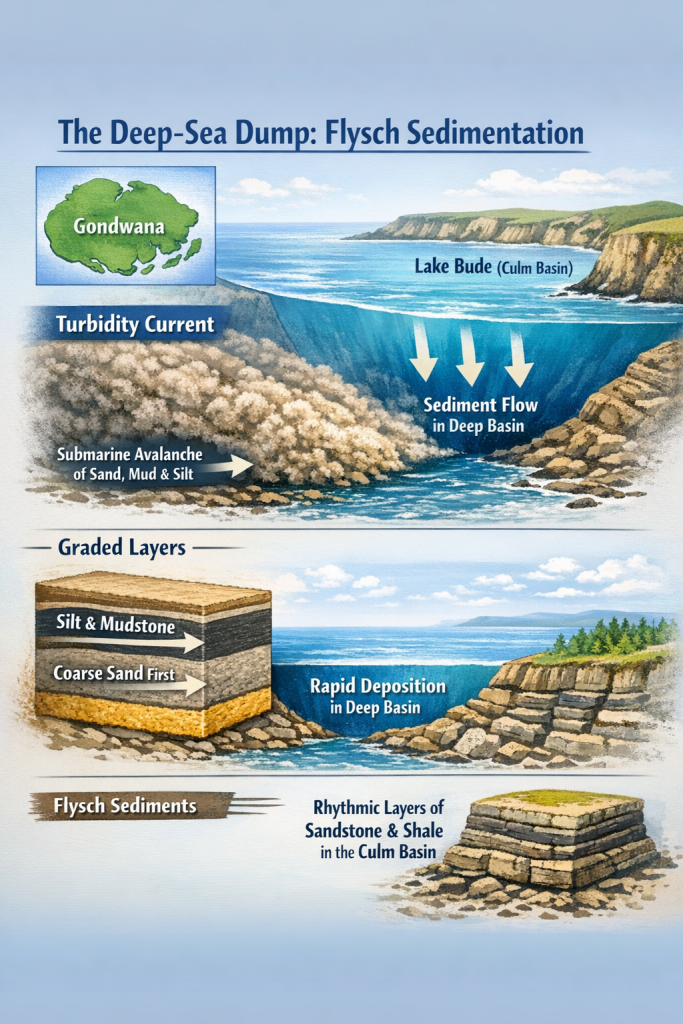

A. The Deep-Sea Dump: Flysch Sedimentation

When these rocks were first forming, the area that is now Cornwall was part of a deep marine basin, often referred to as ‘Lake Bude’ situated near the ancient supercontinent of Gondwana.

- The Process: The rocks were created by vast, episodic submarine avalanches called turbidity currents. These were fast-flowing, dense slurries of sediment—sand, mud, and silt—washed off a massive continental shelf and down a slope into the deep basin.

- The Layers: Each turbidity current pulse settled out rapidly, creating a graded bed:

- Coarse sand settled first, forming the base of the hard sandstone layer.

- Fine silt and mud settled last, forming the top of the layer and the interbedded shale/mudstone.

- The Result: The result is called flysch sedimentation—a rhythmic, layered stack of rock created by high-energy events followed by long periods of calm. Geologists sometimes refer to this ancient water body as the “Culm Basin.”

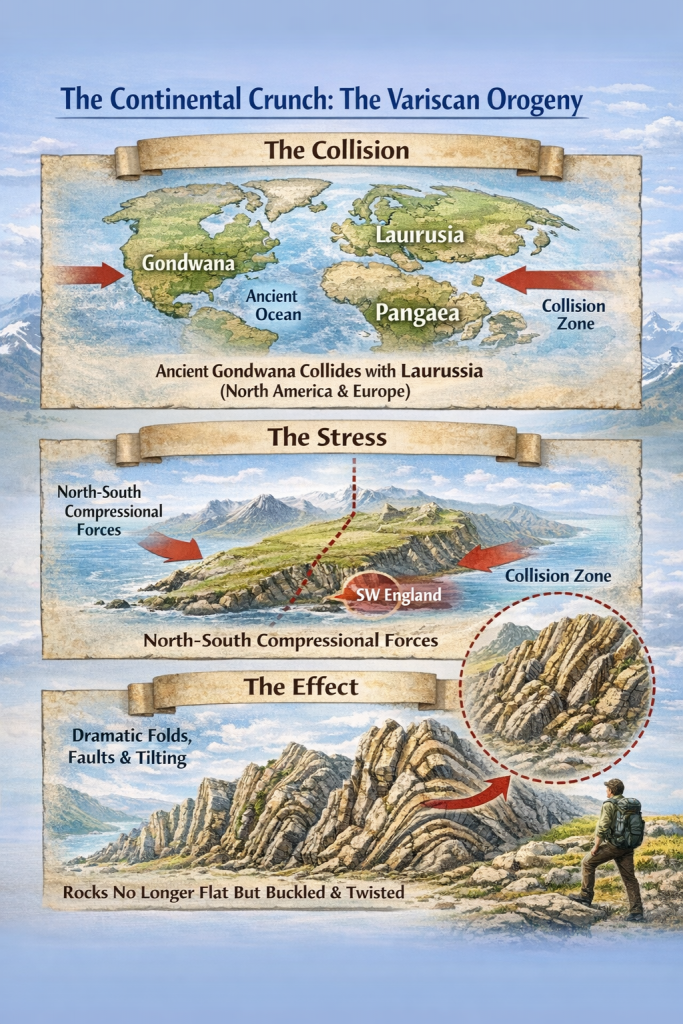

B. The Continental Crunch: The Variscan Orogeny

The second event was a mountain-building phase that dramatically crumpled and contorted these flat-lying layers.

- The Collision: During the Late Carboniferous to Early Permian periods, the ancient supercontinent Gondwana collided with Laurussia (which included North America and Europe). This massive, slow-motion crunch closed an ancient ocean and formed the supercontinent Pangaea.

- The Stress: Southwest England lay on the edge of this vast collision zone. The intense, long-term north-south compressional forces squeezed the sedimentary rocks.

- The Effect: The stress buckled the alternating hard sandstone and soft shale layers like a rug being pushed together, creating the dramatic folds and faults you see today. This is why the rocks are no longer flat but tilted, twisted, and in some places, standing nearly vertical.

3. 🔎 What to Look For: Unmissable Examples Along the Path

The walk is an outdoor classroom for structural geology. Here are the exceptional features to watch out for from the Coast Path (always observe cliffs from a safe distance):

1. Compass Point & Maer Cliffs (The Bude Formation)

Where to look: Stand near Compass Point (where the storm tower is) and look down at the cliffs immediately to the south.

What to spot:

- The Striped Pattern: You will immediately see the cliffs are made of thick, alternating layers—the “stripes” of the Bude Formation. Notice how the layers are tilted steeply into the ground, not lying flat. This shows the first signs of the enormous pressure that squeezed these rocks millions of years ago.

- The Whale’s Back: Look for the distinctive, rounded, resistant slab of rock that juts out from the cliff face or the foreshore near the water line. This curved rock is a clear up-fold (or anticline), giving you a preview of the spectacular folding to come.

- Reading the Ripples: In safer, accessible rock surfaces near the path, look closely for faint ripple marks preserved on the rock tops. These tell you where the original ancient seabed was and the direction the water was flowing 300 million years ago.

Photos by David Evans: SOUTH WEST COAST PATH – a photo tour

This is an ideal introduction to the Bude Formation and deep-water layering.

Black Rock & Widemouth Bay (Flysch Features)

Where to look: Access the beach at Widemouth Bay (check tides!). Walk south towards the large, prominent rock stack known as Black Rock.

What to spot (Low Tide Access Recommended):

- Ancient Landslides: Look for the dramatic rock stack near Black Rock. You will see that it is composed of massive, rounded balls of sandstone mixed into the dark grey mudstone. This unusual mix, called slump breccia, is evidence of a large, sudden mudslide that happened on the ancient deep-sea slope.

- The Sandstone Underside: If you can safely look at the bottom surface of any large, overturned sandstone slabs on the beach, look for bulbous, sinking shapes (load structures). They look like heavy dough pressed into something soft—which is exactly what happened when the heavy sand layers landed on the soft mud.

set in a dark grey succession of siltstone and mudstone.

Photos by David Evans: SOUTH WEST COAST PATH – a photo tour

A superb textbook example of deep-water “flysch” deposits.

3. Transition to the Crackington Formation

Where to look: Continue walking the Coast Path south from Widemouth Bay.

What to spot:

Change in Character: As you walk, you’ll see the cliffs change appearance. The robust, thick sandstone ledges that formed headlands near Bude start to fade away. They are replaced by thinner, darker, more easily crumbled layers of shale and mudstone. You are walking from the mouth of the ancient basin into its deeper, muddier centre.

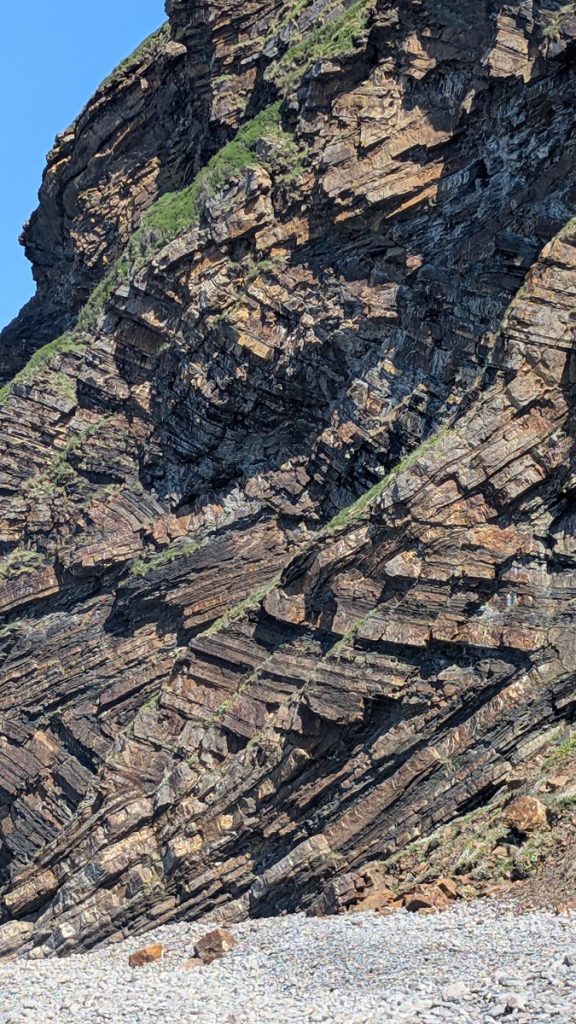

4. Millook Haven – The Famous Zig-Zag Chevron Folds

A must-see geology landmark

Where to look: Descend onto the beach at Millook Haven. The most famous geological sight is best viewed by standing on the beach and looking directly at the northern cliff face.

What to spot:

Hard vs. Soft: Notice how the tough, pale sandstone layers resisted the bending, forming the sharp points and ribs, while the weaker, dark shale layers compressed easily between them, creating the spectacular geometry.

The Geological Accordion: You will see the incredibly tight, sharp zig-zagging folds running up the cliff face. These chevron folds are one of the most photographed geological features in Britain and clearly show the extreme pressure from the continental collision.

5. Castle Point & Pencannow Point

Where to look: Continue on the Coast Path. Look across the large coves (like Great Barton Strand) to the opposite headlands.

What to spot:

- The Gentle Giant: Here, the folds are often broader and more open than the tight zig-zags at Millook. These larger folds help you visualize the vast scale of the Variscan “crunch” that squeezed the entire rock basin.

- Fault Lines: Scan the smooth cliff faces for straight lines or cracks that cut straight across the folded rock layers. These are faults, places where the rock finally snapped under pressure instead of bending.

with Castle Point in the distance

Photos by David Evans: SOUTH WEST COAST PATH – a photo tour

This is one of the best places to visualise how the entire basin was squeezed.

6. Crackington Haven – The Type Section

Where to look: Access the beach at Crackington Haven (check tides!). The cliffs to the north of the beach (near Cambeak headland) are excellent viewing points.

What to spot:

Pencil Rock: Pick up a piece of the dark mudstone (shale) from the beach. Instead of breaking into flat chips, it often breaks into thin, pencil-like fragments. This is called pencil cleavage, a sign that the huge tectonic pressure literally changed how the minerals inside the rock align.

Complex Spaghetti: Look closely at the thin mudstone layers. They are folded into complex, chaotic patterns—much tighter and more intricate than the folds seen elsewhere. This shows multiple phases of squeezing.

Key Takeaway for the Walker

The high, dramatic headlands are built from the tough, resistant sandstones of the ancient deep-sea avalanches, while the beautiful, sheltered coves are formed where the softer shales have been eroded. The scenery you see is a direct result of these ancient geological forces.